|

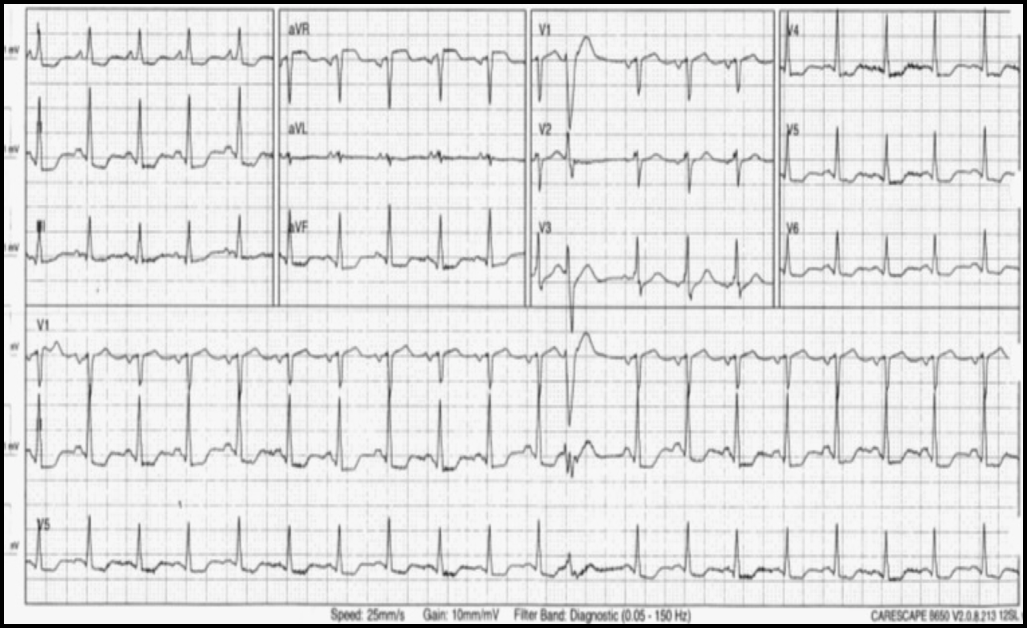

10/2/2019 0 Comments September's ECG LessonCASE: An 83-yo female with a medical history of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and breast cancer presented to an outside hospital after accidental chlorine inhalation. She was mixing chemicals for her pool when she began to feel tightness in her chest. Chest CT showed findings consistent with pneumonitis and inhalation injury. In addition, she also had an elevated troponin of 14 and an EKG demonstrating diffuse ST depressions. Due to worsening respiratory distress, she was intubated and was transferred to our MICU. Here, the echocardiogram showed an ejection fraction of 35-40% with akinesis of the anteroseptal, anterior and apical segments of the myocardium. Consider the ECG shown below:What is your Interpretation?

What is the Significance of this FInding?

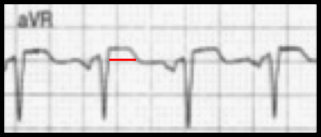

SIGNIFICANCE OF THE aVR SIGN: The aVR sign is characterized by diffuse ST depression combined with ST-segment elevation of >/= 1 mm in aVR. Occasionally, lead V1 also demonstrates elevated ST segments. The aVR sign usually indicates that there is a potentially dangerous underlying pathology in the patient. In patients who present with acute coronary syndrome, the aVR sign frequently indicates severe left main or multivessel coronary artery stenosis. It is not quite a STEMI equivalent but relatively urgent cardiac catheterization is usually indicated. Acute thrombotic occlusion of the left main coronary artery can result in cardiogenic shock and/or sudden cardiac death. We certainly do not want to wait for that to happen. It is important to realize that the aVR sign is not quite specific for left main disease. It can also be seen in other high-risk conditions such as proximal aortic dissection, hemorrhagic shock, massive pulmonary embolism, myocarditis, after cardiac arrest, and in paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. As always, it is important to treat the patient, not data points. Interestingly, regardless of the etiology of the aVR sign, it usually indicates a high-risk condition that warrants urgent evaluation and management. Hospital Course

After resolution of the inhalation injury, the patient underwent semi-elective coronary angiography which revealed severe multivessel disease that was not suitable for interventional management. Guideline-based medical management including aspirin, statin, ACE-inhibitor and beta blocker was initiated. Summary

Dr. Littmann's Lessons to Learn

This case provides an opportunity to discuss two important, popular but somewhat controversial topics of emergency management of cardiac patients: the significance of the aVR sign, and the definition and significance of type 2 myocardial infarction. Drs. Ali and Longerstaey nicely reviewed the aVR sign. In patients who present with typical ACS, the aVR sign can be a marker of severe left main or multivessel coronary artery disease. These patients should receive aggressive medical management including IV beta blocker unless contraindicated, and should undergo relatively urgent cardiac catheterization. In less than typical cases, other high-risk conditions such as type A aortic dissection, hemorrhagic shock and PE should be searched for. In our case, the immediate cause of the aVR sign was severe inhalation injury. A popular concept which also fits this case is the condition termed type 2 myocardial infarction. Type 2 MI is characterized as "myocardial infarction secondary to ischemia that is due to either increased oxygen demand or decreased supply, e.g. stress, anemia, arrhythmias, hypertension or hypotension." Type 1 MI, on the other hand, is caused by acute thrombotic coronary occlusion resulting from plaque rupture or erosion. Our case is a great example that the diagnosis of type 2 MI does not exclude coexisting coronary artery disease. It seams obvious that acute nonthrombotic myocardial injury is more likely to occur in patients with significant coronary stenoses. In the case presented, the ECG changes and troponin elevation appeared to be the result of the stress and hypoxemia of severe inhalation injury. Subsequent coronary angiogram, however, also revealed extensive coronary artery disease. Whether or not patients with type 2 MI should undergo coronary evaluation depends on clinical factors such as age, clinical presentation, the degree of troponin elevation and, importantly, the type of ECG abnormality. In our case, the stress-induced aVR sign and the relatively high troponin appeared to be reasonable indications to pursue non-emergent coronary angiography. References

0 Comments

|

AuthorThis blog represents important ECG lessons that the Emergency Medicine Residents from Carolinas Medical Center (Charlotte, NC) rotating through the Cardiology service encounter. Test your knowledge with them! The esteemed educators Dr. Laszlo Littmann and Dr. Michael Gibbs serve as the primary content editors and course directors. Archives

September 2020

CategoriesAll Bradycardia Cardiology ECG Lesson Heart Block Syncope Ventricular Tachycardia Vtach |

LEGAL DISCLAIMER (to make sure that we are all clear about this):The information on this website and podcasts are the opinions of the authors solely.

For Health Care Practitioners: This website and its associated products are provided only for medical education purposes. Although the editors have made every effort to provide the most up-to-date evidence-based medical information, this writing should not necessarily be considered the standard of care and may not reflect individual practices in other geographic locations.

For the Public: This website and its associated products are not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Your physician or other qualified health care provider should be contacted with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Do not disregard professional medical advice or delay seeking it based on information from this writing. Relying on information provided in this website and podcast is done at your own risk. In the event of a medical emergency, contact your physician or call 9-1-1 immediately.

For Health Care Practitioners: This website and its associated products are provided only for medical education purposes. Although the editors have made every effort to provide the most up-to-date evidence-based medical information, this writing should not necessarily be considered the standard of care and may not reflect individual practices in other geographic locations.

For the Public: This website and its associated products are not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Your physician or other qualified health care provider should be contacted with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Do not disregard professional medical advice or delay seeking it based on information from this writing. Relying on information provided in this website and podcast is done at your own risk. In the event of a medical emergency, contact your physician or call 9-1-1 immediately.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed